Flies as Unsung Heroes: 3 Exclusive Case Studies

Introduction

Are flies pollinators? The question strikes in our minds when we think of pollinators, we usually picture honeybees buzzing from flower to flower. However, there is an astonishingly diverse and effective group of pollinators that often goes unnoticed: flies (order Diptera). In this blog, we will explore how flies contribute to pollination in ecosystems and agriculture, review the scientific data supporting their role, and discuss what this means for gardens and habitats like yours, where you encourage living soil, microbial synergy, and plant communication.

Why flies matter as pollinators

Diversity and reach

Diptera is one of the largest insect orders, with over 125,000 species documented in 110 families. Their great diversity and pervasive presence provide them with distinct benefits as pollinators: they live in habitats where bees may struggle (e.g., alpine, Arctic, shady forest understory), and many species are active in situations less conducive to bees (lower temperatures, low light).

Functional capacity: pollen transfer and flower visitation

Although sometimes underestimated, they can and do effectively transmit pollen. A study evaluating pollen loads across pollinator groups discovered that non-syrphid Diptera (flies other than hoverflies) had no significantly lower pollen loads than syrphid flies (hoverflies) across diverse pollen transport networks.

Another review summarizes how they contribute to floral ecology, plant diversity, and reproductive isolation. A Washington State study published in Science Daily found that syrphid flies accounted for approximately 35% of floral visits on some farms, whereas bees accounted for ~61%.

In summary, they visit flowers, collect pollen, and are often the primary or only pollinators.

Complementarity and resilience

With worldwide pressures on bee populations (disease, habitat loss, pesticide exposure), relying primarily on bees for pollination is problematic. Flies provide an additional pollination service. Cook et al. (2020) identified fly taxa (Calliphoridae, Rhiniidae, and Syrphidae) with high potential for managed pollination to supplement bee pollination in horticultural crops. This shows that these insects can help to strengthen pollination systems.

How fly pollination works: mechanisms & specializations

Flower visitation behaviour

Many flies visit flowers for nectar, pollen, or other resources (such as secretions), though their reasons may differ from bees, who collect pollen for brood provisioning. Syrphid flies (hoverflies) mimic bees in coloration and behavior, which may shield them from predators and allow them to access flowers more easily.

When flies land on flowers, particularly hairy-bodied species, pollen grains cling to their bodies (legs, thorax, and abdomen) and go to nearby flowers. Unlike bees, many flies do not aggressively pack pollen into specialized structures; therefore, more pollen may be ‘available’ for transfer (rather than gathered for brood).

Adaptations in plant-fly relationships

Some plants and flies have developed remarkable mutualisms, or even misleading interactions. A study of an alpine plant population discovered that the plant’s camouflaged blossoms were only visited by anthomyiid flies (rather than bumblebees), yet the plant nonetheless produced a lot of fruit and seeds due to the high frequency of fly visits. Plants that rely on fly pollination have evolved to attract flies through deceptive blossoms that resemble fungus or decaying debris, particular flower morphologies tailored to fly size/behavior, and unique scent/color signals.

Efficiency and limitations

While flies can be effective pollinators, they are often less efficient than bees for specific crops or flower kinds. In a study of two Salvia species, which are normally pollinated by bees, flies delivered pollen and made stigma contact, but bees were still more efficient per visit.

However, efficiency is heavily dependent on context, including flower form, fly body size, ambient variables (temperature, light), and the availability of alternative pollinators. Flies frequently serve as principal pollinators in situations where bees are uncommon (for example, cold or high altitude).

Ecological and agricultural significance

Wild plant reproduction & ecosystem stability

Flies are the major pollinators in environments with low bee diversity and severe environmental circumstances, such as the Arctic. A 2016 study discovered that muscid flies (members of the Muscidae family) were important pollinators in the High Arctic, challenging the notion that bees are everywhere.

Furthermore, flies play an important role in flowering plant reproduction, enabling higher trophic levels (pollinated plants → herbivores → predators) and ecosystem resilience.

Agricultural and horticultural potential

The role of flies in agriculture is receiving more attention. The “fly pollination” study for Australian horticulture emphasizes that flies can supplement or even partially replace bee pollination in some crops, such as when bees are unavailable or when blossoms are less appealing to bees.

Key advantages include:

- Flies have shorter foraging times, may function in colder or low-light environments, and rely less on pollen for brood rearing (requiring less specialization)

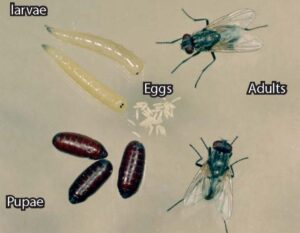

- Some fly species are mass-produced or have manageable life cycles, making them suitable for pollination services

- Using a diverse range of pollinators minimizes the likelihood of pollination failure if one group (for example, bees) diminishes

However, practical challenges remain, such as matching fly body size/morph to flower architecture, logistics for rearing, and ensuring that they affect pollen transfer (rather than nectar robbing or floral feeding). In comparison to bee-pollination research, the literature remains scarce.

Implications for gardeners and living soil advocates

Given your interest in living soil, microbial synergy, and different ecosystems, the role of flies as pollinators provides several intriguing takeaways for our blog readers:

1. Design for diversity

Many gardeners focus solely on attracting bees but planning planting schemes that also attract flies (hoverflies, syrphids, and mid-sized dipterans) improves pollination security. For example, add flowers with accessible nectar/pollen, variable bloom dates, and shaded/damp areas that flies may prefer.

2. Avoid over-cleaning

Some of them are deterred by meticulously groomed, sterile gardens. Maintaining some “messy” microhabitats (leaf litter, bare soil patches, decaying wood) can feed fly larvae (which frequently have saprophagous or predatory life stages) and hence increase adult fly populations.

3. Flower morphology matters

Plants having open or shallow flowers, as well as scents/hues that they prefer (dull colors, accessible disk blooms), can boost fly visitation. While bees prefer bright colors and deep corollas, flies may visit less visible flowers, especially in cooler or cloudier weather.

4. Pollinator interactions and plant health

Because they can visit in cooler or less favorable conditions (early morning, late afternoon, cloudy days), they fill in gaps when bees may be inactive. This means your garden’s pollination window is larger and more effective.

Case studies and examples

1. Dioecious plants pollinated by flies

In a fascinating study, researchers investigated the interactions between two dioecious plant species, which produce distinct male and female flowers. The research examined the significant contribution of generalist flies, which are members of the order Diptera, in the intricate process of pollination. The study’s findings illustrated that these fly species engaged with both male and female flowers with remarkable frequency, indicating their dual role in the reproductive cycles of flowering plants. This behavior underscores their effectiveness as pollinators, as they facilitate the transfer of pollen between different genders of flowers, promoting outcrossing.

Outcrossing is vital for enhancing genetic diversity within plant populations, which in turn increases resilience against diseases and environmental stresses. The evidence suggests that generalist flies are not merely passive visitors; they actively contribute to the genetic mixing that is essential for the survival and adaptation of plant species. Furthermore, this emphasizes the indispensable function that insect pollinators, such as these flies, play in sustaining ecological balance. By ensuring a robust pollination network, they help maintain healthy ecosystems, support biodiversity, and enhance the overall productivity of various habitats.

2. Flies in managed horticulture

In the evaluation conducted in Australia, researchers identified a diverse array of insect species that hold potential for enhancing managed pollination services. Specifically, a total of 11 calliphorid fly species were recognized, along with two species from the Rhiniidae family and seven syrphid species.

These species were selected based on a comprehensive analysis of several key factors. Firstly, their physical characteristics, such as hairiness and body size, were closely examined, as these traits can influence their efficiency in collecting and transferring pollen. Additionally, the foraging behavior of each species was scrutinized, with an emphasis on their patterns of movement and pollen collection strategies within various floral environments.

Furthermore, the life histories of these pollinators were taken into account, focusing on factors such as developmental stages, reproductive patterns, and ecological roles. This multidimensional approach underscores the importance of selecting pollinators that not only contribute to pollination but also exhibit traits advantageous for supported management practices in agricultural and natural ecosystems. The findings highlight a promising avenue for enhancing pollination efforts through the strategic use of these species in managed settings.

3. Alpine pollination

The alpine plant Fritillaria delavayi is characterized by two distinct populations that exhibit notable differences in their flower coloration and the types of pollinators they attract. One population features vibrant yellow flowers, which serve as a beacon for bumblebees that frequently visit these blooms seeking nectar. In contrast, the other population possesses flowers that are subtly camouflaged within their environment, making them less noticeable and primarily attracting a different group of pollinators – flies, specifically from the family Anthomyiidae.

Interestingly, despite the camouflaged population primarily relying on fly visits for pollination, it has been observed to produce a comparable seed set to that of the yellow-flowered population. This surprising outcome can be attributed to the higher frequency of visits by these tiny creatures to the camouflaged flowers. The increased number of fly interactions compensates for the absence of bumblebee visits, demonstrating that under certain conditions, alternative pollinators can effectively fulfill the role of seed production just as well as more traditional pollinators like bumblebees.

Challenges and knowledge gaps

While the evidence is convincing, a few obstacles remain:

- Data scarcity: Compared to bees, significantly fewer studies have measured fly pollination efficiency, pollen transfer per visit, and agricultural production effects

- Flower-fly compatibility: Not all flowers are appropriate for them (for example, particularly deep corollas and highly specialized bee flowers). Understanding morphological compatibility is key

- Management logistics: The employment of flies as “managed pollinators” in greenhouses and orchards is still in its early stages. More research is needed on reproduction, release timing, and integration with current pollinator systems

- Perception and education: Many gardeners and farmers regard flies as pests; changing this perspective is required to properly deploy them

Final Thoughts

Flies are much more than just nuisance insects; they play critical roles in pollination across various ecosystems, from remote Arctic regions to agricultural fields. Their diversity, resilience, and complementary behaviors make them invaluable allies for gardeners who care about ecological resilience, healthy soil, and biodiversity. By understanding how and when flies pollinate, as well as by creating habitats that support them alongside bees and other beneficial insects, we can develop more resilient, productive, and environmentally sound plant-pollinator systems.

Disclaimer

The content provided on this website is purely for educational purposes. We are neither nutritionists nor do we intend to mislead our readers by providing any medical or scientific information.