Why Pakistani Mangoes? 5 Exclusive Differences

Introduction

Few fruits inspire as much admiration and affection as mangoes (Mangifera indica). The mango, globally known as the “King of Fruits,” is more than just a sweet treat; it is a nutritional powerhouse, a cultural symbol, and a scientifically fascinating species. It has a 4,000-year history, spans continents, and has a significant impact on agriculture, health, and worldwide trade. This blog delves into the scientific, nutritional, ecological, and cultural aspects of mangoes, exploring why they are so widely admired worldwide.

Origins and Evolutionary History

Mango trees are part of the Anacardiaceae family, which includes cashew and pistachio. Mangoes are native to the Indo-Burmese region and are said to have originated in northeast India and Myanmar. Fossil evidence of their presence dates back 25-30 million years, demonstrating their long-standing importance in tropical ecosystems.

Humans first domesticated mango plants at least 4,000 years ago. Mangoes are described in ancient South Asian texts, such as the Upanishads and early Ayurvedic teachings, as emblems of prosperity, fertility, and divine blessing, in addition to their nourishing properties. Mango seeds moved to East Africa via maritime trade around the 10th century, and Portuguese explorers brought them to Brazil and the Caribbean in the 16th century. Mangoes are now grown in over 100 tropical and subtropical countries, making them one of the world’s most frequently produced fruits.

Botanical Characteristics

The mango tree is a long-lived evergreen that can reach 30-40 meters and live for generations in ideal conditions. Its deep taproot lets it survive in dry weather, while its dense canopy provides shelter and shade.

The leaves are leathery, lance-shaped, and high in polyphenols, which help the tree defend against pests. Mango blossoms are tiny, fragrant, and borne in huge clusters known as panicles. Mango trees rely significantly on insect pollinators such as bees and flies; therefore, only a small percentage of blossoms produce fruit.

The fruit is botanically defined as a drupe, a fleshy fruit with a hard stone that encloses the seed. Depending on the kind, mangoes can be round, oval, or kidney-shaped, with skin colors ranging from green to golden yellow to deep red. Each variety has its own unique combination of sugars, acids, and volatile compounds that contribute to the mango’s distinct aroma and flavor.

Genetic Diversity and Cultivar Development

There are around 1,500 recognized mango varieties worldwide, but only a small percentage are economically farmed. India alone recognizes hundreds of regional variants, such as Alphonso, Dasheri, Langra, and Kesar. Each cultivar varies in fiber content, sweetness, juiciness, and pest resistance.

Modern breeding initiatives aim to improve shelf life, disease resistance, and export quality. Researchers employ marker-assisted selection and genomic mapping to find characteristics associated with fruit size, flavor chemistry, and abiotic stress tolerance. Hybrid cultivars are also being created to adapt mangoes to climates outside the conventional producing zones, assuring the long-term development of farming.

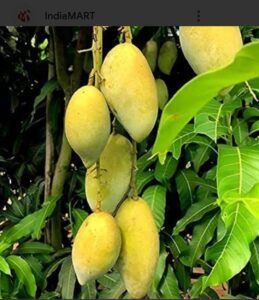

Pakistani Mango Varieties: A Global Benchmark of Flavor and Quality

Pakistan is home to some of the world’s finest mangoes, renowned for their distinctive aroma, sweetness, and velvety texture. The country’s unique geography—fertile alluvial plains along the Indus River, long sunny summers, and monsoon rains—makes it an ideal location for mango farming. Pakistan produces approximately 1.8-2 million tons of mangos each year, making it one of the world’s largest producers, with exports to the Middle East, Europe, and North America.

1. Sindhri

Sindhri, also known as the “Queen of Mangoes,” is one of the season’s earliest mangoes, collected in May and June. It is oval-shaped, golden yellow, and highly delicious with little acidity. Its cellulose-free pulp makes it a popular choice for desserts and fresh foods.

2. Chaunsa

Chaunsa is possibly Pakistan’s most well-known export cultivar, valued globally for its incomparable sweetness and deep aroma. Chaunsa, available in July and August, has a delicate, fiberless pulp that is great for juices and smoothies. There are several subtypes, including White Chaunsa and Black Chaunsa, each with its own distinct flavor notes.

3. Anwar Ratol

Anwar Ratol is a small but flavorful fruit known for its deep sweetness and strong texture. Its limited season in June makes it a sought-after delicacy among mango enthusiasts. Because of its powerful aroma and smooth texture, it is frequently referred to as a “luxury mango.”

4. Langra

Langra has green skin, even when ripe. The pulp is golden, juicy, and somewhat tangy, with a good mix of sweetness and acidity. Langra is widely grown in Punjab and is particularly popular among local people.

5. Dussehri

Dussehri, a medium-sized mango with a yellow peel and a mild scent, has a long harvest window spanning June and July. Its soft, juicy pulp allows it to be consumed fresh or processed into pulp for juices and purees.

Comparing Pakistani Mangoes with Global Cultivars

Indian Varieties

India, the world’s top mango producer, shares several kinds with Pakistan due to their mutual heritage. The famed Alphonso from Maharashtra is well-known for its saffron-colored flesh, powerful aroma, and long shelf life. Alphonso is less sweet than Chaunsa, but with more citrus and resin overtones.

Thai Varieties

Thailand is famous for Nam Dok Mai and Keo Savoy, which are elongated, fiberless, and extremely delicious. These cultivars are commonly served slightly under-ripe with sticky rice. While they have a similar smoothness to Sindhri, their flavor profile is more flowery and lighter.

Mexican Varieties

Mexico leads the US mango market with types including Ataulfo (Honey mango) and Haden. Ataulfo is petite, golden, and creamy, similar to Anwar Ratol in size but with a milder flavor. Haden and Kent types are larger and more fibrous, making them better suited for long-distance shipment, but they lack Chaunsa’s deep sweetness.

Egyptian Varieties

Egypt’s Zebda and Alphonse mangoes are medium-sized, fibrous, and moderately sweet. While popular in local markets, they have less aroma than Pakistani and Indian varieties.

Why Pakistani Mangoes Stand Out

Climate Advantage

Extended periods of warm summer weather, characterized by high daytime temperatures and notable fluctuations between day and night temperatures, create ideal conditions for the accumulation of sugars in certain crops. This significant diurnal temperature variation allows plants to photosynthesize more effectively during the hot days, while the cooler nighttime temperatures help to enhance the concentration of sugars in their fruits and foliage. As a result, this climatic pattern plays a crucial role in enhancing the sweetness and overall quality of various agricultural products.

Soil Richness

The Indus Basin is renowned for its exceptionally fertile and mineral-rich soil, which plays a crucial role in enhancing the quality of mangoes grown in the region. This unique soil composition not only provides essential nutrients that promote healthy tree growth but also contributes to the development of sweet, flavorful mangoes. The fertile land, nourished by the waters of the Indus River and its tributaries, creates an ideal environment for mango cultivation, resulting in some of the most sought-after varieties in the world. The combination of natural resources and agricultural practices in this basin ensures that the mangoes produced here are of superior quality, making them a prized commodity in both local and international markets.

Diversity

Pakistan is known for its diverse agricultural landscape, which allows for the production of around 200 different varieties of crops and agricultural products. However, only a select few of these varieties meet international standards and are exported to global markets. This limited range of exports highlights both the potential and challenges present in the country’s agricultural sector.

Taste Profile

Pakistani mangoes are renowned for their exceptional quality and unique characteristics. They are typically fiberless, making them incredibly smooth and a delight to eat. One of their standout features is their remarkable sweetness, which is often accompanied by a rich, aromatic fragrance that enhances the overall tasting experience. These attributes make Pakistani mangoes highly sought after by international consumers, who appreciate both their flavor and texture. The country’s diverse climate and soil conditions contribute to the distinct taste of these mangoes, solidifying their reputation in the global market.

Cultural Heritage

The mango orchards in Multan, Sindh, and Rahim Yar Khan hold a significant place in the cultural fabric and local identity of these regions. These orchards are not just sources of fruit; they are woven into the very essence of community life, showcasing a rich tradition that celebrates harvest festivals and local customs. The mango season transforms these areas into vibrant hubs of activity, attracting visitors and gathering families as they indulge in the delicious varieties of mangoes that are grown there.

Moreover, the economic impact of these orchards cannot be overstated. They provide employment opportunities for many local farmers and laborers, promoting livelihoods and enhancing the regional economy. The trade of mangoes, both locally and internationally, supports a network of businesses, from transportation to processing and retail. Thus, the mango orchards are not only central to agricultural practices but are also vital to preserving the unique heritage and economic vitality of Multan, Sindh, and Rahim Yar Khan.

Nutritional Composition

Mangoes are often called a “superfruit” due to their dense nutritional profile. A standard cup of sliced mango (about 165 grams) provides:

- Calories: 99

- Carbohydrates: 25 grams (mostly natural sugars like glucose, fructose, and sucrose)

- Dietary fiber: 3 grams

- Vitamin C: 67% of the daily value (DV)

- Vitamin A: 10% DV (as beta-carotene)

- Folate: 18% DV

- Vitamin E: 9% DV

- Potassium: 6% DV

- Magnesium: 4% DV

The bright orange-yellow color of ripe mangoes comes from carotenoids, including beta-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin, which support vision and function as antioxidants. Additionally, the peel and seed kernel contain polyphenolic compounds such as mangiferin, catechins, and gallotannins, which have been studied for their potential therapeutic properties.

Health Benefits Supported by Science

1. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties

Mangoes are high in mangiferin, a xanthone molecule that has powerful antioxidant properties. According to studies, mangiferin may protect against oxidative stress, reduce inflammation, and minimize the risks of chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

2. Digestive Health

Mango fiber helps healthy bowel movement, while enzymes like amylase help break down complex carbohydrates into simpler sugars, which aid digestion. Traditionally, mango pulp and leaves were used to treat dysentery and diarrhea.

3. Eye Protection

Carotenoids such as lutein and zeaxanthin build in the retina and filter out harmful blue light, reducing the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Beta-carotene also promotes vitamin A production, which is necessary for night vision.

4. Immune Support

Vitamin C boosts the immune system by increasing white blood cell activity, improving iron absorption, and defending against free radicals. Mangoes contain folate, which is important for healthy cell division during pregnancy and infancy.

5. Heart Health

Potassium and magnesium help to maintain normal blood pressure, while soluble fibers help to control cholesterol levels. According to research, mango polyphenols may lower arterial inflammation, which contributes to cardiovascular health.

6. Skin and Hair Nourishment

Vitamin A regulates sebum production and protects epithelial tissue, whereas vitamin C promotes collagen synthesis, keeping skin firm and hair strong. Mango seed butter, used in cosmetics, has natural emollient qualities.

Mangoes in Traditional Medicine

Ayurvedic practitioners have long recommended several portions of the mango tree for medicinal purposes. To manage blood sugar, leaves were brewed into teas, bark extracts were used as an astringent, and fresh mangoes were administered to prevent heatstroke. Mangoes were revered in Chinese medicine for their capacity to rid the body of impurities and improve digestion. Modern pharmacological research is still validating many of these traditional uses, including the anti-inflammatory and antibacterial capabilities of mango bioactives.

Ecological Role of Mango Trees

Aside from its fruit, mango trees benefit biodiversity and local ecosystems. Birds can nest in their enormous canopies, and pollinators are drawn to the nectar-rich blooms they produce. Fallen leaves contribute to soil organic matter as they degrade. Mango trees are drought-tolerant and long-lived; therefore, they play an important role in agroforestry systems, providing shade for intercrops and contributing to carbon sequestration.

Global Production and Trade

Mango farming occurs throughout Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Oceania. India leads the globe in mango production, accounting for about 45% of worldwide output, followed by China, Thailand, Indonesia, and Mexico. While India eats the majority of its production locally, Mexico and Peru dominate mango exports to North America and Europe. Pakistan, Egypt, and Brazil are all big exporters.

The international mango business is worth billions of dollars each year, with demand constantly increasing as customers seek unusual and health-promoting fruits. Challenges include post-harvest losses of up to 30% in tropical regions due to inadequate storage, as well as the need for improved cold chain logistics to protect fruit quality during transit.

Post-Harvest Science and Technology

Mangoes are climacteric fruits, which means they continue to ripen after harvest thanks to ethylene production. Post-harvest treatment practices are intended to slow ripening and extend shelf life. Methods include:

- Hot water treatment kills fruit fly larvae and reduces fungal diseases

- Modified atmospheric packing reduces oxygen exposure and slows respiration

- Temperature and humidity are controlled within ripening chambers

- To reduce moisture loss, edible coatings can contain chitosan or aloe vera

These advancements reduce spoilage, improve food safety, and assist exporters in meeting international requirements.

Mangoes in Culinary Traditions

Mangoes are popular in many different cuisines around the world. In South Asia, they are eaten fresh, combined into lassi, or pickled with spices. I do have a video of Pakistani achar on my YouTube channel. In Mexico, mango slices are transformed into a tart street snack by adding chile and lime. Thai cuisine emphasizes mango sticky rice, but Caribbean chefs serve mango salsa alongside seafood. Chefs today experiment with mango reductions, sorbets, smoothies, and even savory curries, exhibiting the fruit’s extraordinary adaptability.

Cultural and Symbolic Importance

Mango trees and mangoes have great cultural importance. Mango leaves are used to decorate entrances during Hindu festivities as a symbol of prosperity and fertility. Mangoes’ sweetness has been associated with love and longing by poets throughout South Asia. According to Buddhist legend, the Buddha meditated under mango orchards, achieving peace and enlightenment. Mango designs can still be found in textiles, art, and jewelry today, indicating that the fruit is a timeless cultural icon.

Sustainability and Future Outlook

As climate change worsens, mango agriculture faces difficulties such as unpredictable rainfall, heat stress, and pest outbreaks. To maintain production, scientists are developing climate-resilient mango cultivars, implementing precision irrigation systems, and embracing organic farming techniques.

Urban agricultural programs are also introducing dwarf mango varieties appropriate for rooftop and backyard gardening, hence increasing access to fresh fruit. Furthermore, byproducts such as mango peels and seeds are being repurposed as animal feed, biodegradable plastics, and nutraceutical supplements, assuring a circular and sustainable mango economy.

Conclusion

The mango is more than simply a fruit; it represents biodiversity, cultural legacy, nourishment, and global connectivity. Mangoes continue to inspire joy and curiosity everywhere, from ancient orchards in South Asia to supermarket shelves around the world. Their rich chemistry promotes human health, their production helps rural economies, and their symbolism connects cultures across continents.

As research advances and production adjusts to new environmental realities, these bounties will continue to thrive as a cherished delicacy and a scientifically relevant crop. For scientists, farmers, and food enthusiasts alike, the mango certainly lives up to its moniker of “King of Fruits.”

Disclaimer

The content provided on this website is purely for educational purposes. We are neither nutritionists nor do we intend to mislead our readers by providing any medical or scientific information.